Young adults

Key findings

- Young adults are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system compared to other age groups and reoffend at a higher rate. The combination of high offending and high potential for desistance supports a focus on 18-24 year olds.

- There is evidence to support certain types of intervention; attention should be given to avoiding sentences and interventions which delay or damage the transition to a more pro-social identity and the processes of desistance that are particularly acute at this time.

- Gaining employment is a major milestone into adulthood, and thus a key issue to address for young adults.

- There is research support for treating 18-24 year olds as a distinct group, recognising their differing levels of maturity and the evidence that brain development continues into the twenties, impacting upon self-control, consequential thinking and appraisal of risk. Adverse life experiences such as trauma, deprivation, violence or bereavement can harm brain development, and there has been chronic under-recognition of traumatic brain injury.

- The research evidence highlights the need to avoid a one-size-fits-all young adult strategy. For example, young adult women mature at a different rate and manifest maturity in a different fashion than young adult men, and they tend to have differing needs and life experiences.

Background

Young adults move through many profound transitions between the ages of 18-24. If they have not already, this is the time period where they leave education for employment, move into long (or longer) term romantic relationships sometimes including parenthood, move from the parental or care home to independent living, and exchange various childhood agency involvement in their lives with adult services or independence. Culturally, young adults are expected to behave differently to teenagers, and when they encounter the criminal justice system, they are treated as adults.

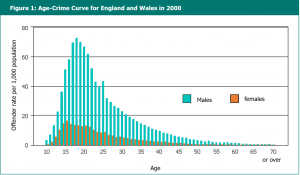

18-24 year olds represent one-tenth of the general population but are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. The benefits of successfully helping young adults to desist from offending are potentially very large. The volume of crime committed by this age group is higher than for any other adult age group, providing an opportunity for large reductions in the total number of crimes committed.

Key statistics are as follows:

- there were 20,627 adults in the 18-24 age category serving community sentences or suspended sentence orders on 31 December 2020, representing 22 per cent of all such cases. In 2010, the equivalent figure was 34 per cent

- of those young adults supervised in the community on 30 June 2018 with a completed OASys (Offender Assessment System), 30 per cent had maturity issues (males only), nine per cent had a mental health problem and 32 per cent had a learning disability or challenge

- of those young adult supervised in the community on 30 June 2018 with a completed OASys, 72 per cent had lifestyle and associates identified as an offending-related need, thinking and behaviour was identified in 62 per cent of cases, and education, training and employment in 55 per cent of cases.

Summary of the evidence

Potential for desistance

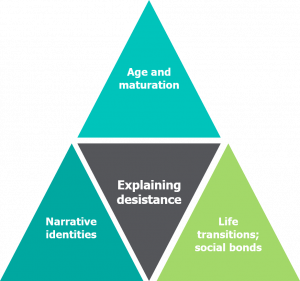

Young adults are at a pivotal moment in their capacity for offending and desistance from crime. They are an age group that commits a relatively high number of offences, but they are also the age where most of those that desist from crime begin to do so. The transitions from a childish self-identity to an independent, grown-up and more responsible identity are already happening and can be encouraged by professionals to enable swifter desistance from offending.

The combination of high offending and high potential for desistance supports a focus on 18-24 year olds. Appropriate approaches (supported by research evidence) can include the following:

- structured programmes to enhance thinking skills and regulate emotions, including cognitive skills and anger management interventions

- interventions designed to strengthen family bonds

- education, training and help in finding employment

- activities that encourage people to take responsibility and build a positive identity, including taking on peer support roles, and restorative justice.

Conversely, we know that young people do not tend to benefit from more punitive or deterrence-based approaches, especially where the punitive elements do not fit with how we understand rewards and sanctions to work with immature or younger people, approaches that fail to help people build skills for the future, or interventions that reinforce a criminal identity.

The transition to a more pro-social identity can be slowed by inappropriate sentences and by transitions between agencies, particularly where positive, respectful and trusting relationships have been established with individual practitioners. Younger adults, in particular those aged between 18 and 20, have been found to benefit more from community orders than short custody orders, compared to other age groups except for those over 50 years of age. Where a custodial sentence is appropriate, it has been highlighted that the term should reflect the increased impact on the young adult’s life, particularly in the way that it might delay or damage processes of desistance that are particularly acute at this time, such as in securing education or employment, parenting of very young children, and in deprivation of developmental opportunities for the young adult.

Education, training and employment

Between the ages of 18 and 24, young adults are usually expected to move out of education and into employment. This transition is a major life milestone, with many young adults working full time for the first time in their lives. At this crucial junction, young people are forming their adult identities, finding employment and changing their perception of themselves from dependent, such as students, to independent, making their own money. Without this transition being successfully completed, young adults are missing a major milestone into adulthood and risk cementing a less pro-social self-identity. Employment is therefore a key issue for young adults, not just for the positive financial position it can confer or to keep them occupied, but as a route out of offending and to a non-offending identity.

Treating 18-24 year olds as a distinct group

There is research support for treating 18-24 year olds as a distinct group, helping to fully apply the knowledge we have about the approaches and interventions which are likely to be most effective, while recognising that chaotic lifestyles, developing maturity levels, and difficulties building trusting relationships can impact upon engagement.

Maturity is supposed to be taken into account in terms of culpability for prosecution and as a possible mitigating circumstance in sentencing. However, a 2021 report by the Magistrates Association found that maturity was not often raised in magistrates courts and where it was it tended to be at the pre-sentence report (PSR) stage. Even when raised in PSRs, maturity assessment was often poorly linked to the offence, and with little explanation to the recommended sentence.

Over the last few decades, the evidence has grown that brain development continues into the twenties and that young adults should not necessarily be treated as fully mature, with varying abilities to plan, control behaviour and exercise emotional restraint. The last sections of the brain to develop, including the pre-frontal cortex, are central to emotional self-regulation and consequential thinking. Adverse life experiences such as trauma, deprivation, violence or bereavement can harm brain development. There has also been chronic under-recognition of traumatic brain injury, which can lead to difficulties in relation to cognition, memory, social communication, and self-regulation of emotions and behaviours, which can be further exacerbated by co-occurrence with other neurodevelopmental problems and risk factors.

A fully personalised approach

The research evidence highlights the need to avoid a one-size-fits-all young adult strategy. For example, young adult women mature at a different rate and manifest maturity in a different fashion than young adult men, and they tend to have differing needs and life experiences, for example being less likely to return to family or secure housing upon release from custody. Consequently, a single approach, driven by the needs of young adult men, will not cater sufficiently to young adult women.

In the 2017 Lammy Review, those young adults of black ethnicity and those that identified as Muslim reported pernicious stereotyping and differential treatment. Stereotypes about ethnic minority service users can be harmful, especially to an age group that are in the process of forming their own self-identities. For example, if young black men are assumed to be involved with gang activities or if young Muslim men are assumed to be at risk of radicalisation, this can lead not only to efforts being wasted where such issues do not exist, but also to alienation and a move away from the development of a more pro-social identity.

The Children and Social Work Act 2017 now extends entitlement to statutory support up to the age of 26 for those leaving care. Care leavers are more likely to struggle with lack of family support, feelings of rejection, abandonment and bereavement, and to lack resources when it comes to finding work and housing. They may also lack established healthy peer relationships.

- higher levels of education, training and employment need for younger adults

- sufficient services less likely delivered for younger adults in relation to both drug misuse and alcohol misuse.

Barrow Cadbury Trust. (2005). Lost in Transition: A Report of the Barrow Cadbury Commission on Young Adults and the Criminal Justice System. London: Barrow Cadbury.

Hillier, J. And Mews, A. (2018). Do offender characteristics affect the impact of short custodial sentences and court orders on reoffending?, Ministry of Justice Analytical Summary. London: Ministry of Justice.

Justice Committee. (2018). Young adults in the criminal justice system. London: House of Commons.

Magistrates Association. (2021). Maturity in the magistrates’ court: Magistrates, young adults and maturity considerations in decision-making and sentencing. London: The Magistrates Association.

McNeill, F. and Whyte, B. (2007). Reducing Reoffending: Social Work and Community Justice in Scotland. Cullompton: Willan.

Revolving Doors. (2021). Evidence review: diverting young adults away from the cycle of crisis and care. London: Revolving Doors Agency.

Transition to Adulthood Alliance. (2015). Effective approaches with young adults: a guide for probation services. London: Barrow Cadbury Trust.

Young Review. (2012). The Young Review: Improving outcomes for young black and/or Muslim men in the Criminal Justice System. London: The Young Review.

Back to Specific sub-groups Next: Women