Women

Key findings

- Women offend for different reasons than men, and often emphasise different factors when they successfully desist from offending.

- Women from an ethnic minority background can have different needs to both ethnic minority men, and white women.

- Custody can be particularly damaging for women, and they have been disproportionately affected by the introduction of post-sentence supervision and consequent recall or commitment to custody.

- Women’s centres can effectively engage those who attend, addressing their specific needs.

- Relationships are very important to the rehabilitation of women and can be both protective or criminogenic factors.

Background

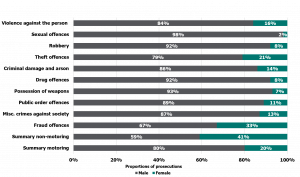

Women are a minority in the criminal justice system, representing about five percent of those held in custody and about 10 percent of those supervised in the community. The causes of offending, types of crimes committed, and routes out of offending can differ between men and women:

- women commit less violent, serious or organised crime, but more acquisitive crime

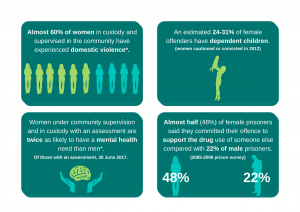

- women are more likely to have mental health issues and to suffer from drug addictions

- women are also more likely to be victims of crime, with histories of violence and abuse.

These differences highlight the need for women-centred provision. However, because the bulk of people in the criminal justice system are men, the system is much more focused on providing services for this majority group.

The 2007 Corston report concluded that the issues that lead women to offend are more likely to be addressed in the community using casework, support and treatment. It was noted that prison is unlikely to have any value as a deterrence, recognising that the vast majority of women do not commit crime and, of those that do, only a tiny minority commit crimes of violence.

In early 2021, the Government published a Concordat of Women in or at risk of contact with the Criminal Justice System which sets out how Government and other partners should work together at national and local levels to identify and respond to the needs of women, supporting them ‘to turn their lives around for the benefit of their victims, their families, wider society, and for the women themselves’.

Summary of the evidence

Women offend for different reasons than men

Violent crime by women is associated with alcohol abuse, while acquisitive crime (and soliciting) is associated with serious drug abuse. There are also links between mental health issues and violence by women, and women are often involved in the justice system due to their repeated victimisation. Many women have multiple, acute and unmet needs – cuts to services have resulted in a lack of crisis support for women, particularly around mental health and safe residential facilities for those fleeing violence.

Sentencing and recall

Custody has been found to have a detrimental impact for women. Even incarceration of a few weeks can leave women highly vulnerable to losing jobs, housing and even their children. Women who offend are often the primary or sole carer for children and this should be taken into consideration as a mitigating circumstance when passing sentence under the UN Bangkok Rules, the sentencing guidelines, and as established under case law. Long distances, the unsuitability of prisons as a place for children, and cost can make it difficult for women to be visited by their children while they are in custody. Prison can also be traumatising – the rates of self-harm in custody are nearly five times higher for women than men. The Corston report found that some women were being sent to prison as a ‘place of safety’ or ‘for her own good’, as well as a way of accessing services such as detoxification. Baroness Corston was clear that these reasons for sending women to custody needed to stop.

Women tend to have shorter prison sentences than men, and so the introduction of post-sentence supervision (PSS) and the new licence periods has meant that proportionately more women are serving the new licence period in which they can be recalled (and also a PSS period during which they can be ‘committed to custody’ for breach). A greater proportion of women are now being recalled, and the reasons for recall are different from men – women are half as likely to be recalled due to a further charge, but about 20 per cent more likely to be recalled for failing to keep in touch.

Reducing reoffending

Evidence suggests that women’s reoffending can be reduced through:

- substance misuse treatment, especially when using cognitive-behavioural therapy

- gender-responsive cognitive behaviour programmes that emphasise strengths and competencies, and skill acquisitions

- community opioid maintenance while women are in treatment

- booster programmes in the community that follow up on earlier treatment.

Serious mental health issues, particularly those that are factors in violent offending, need to be stabilised before work on addressing other needs.

Further evidence indicates that while the desistance process is similar for women and men in relation to maturation, transitions, changed lifestyles and associates, the focus is often different. More specifically, men that desist tend to focus on personal choice and agency, while women desisters focus more on relational aspects, typically parental attitudes, assumption of parental responsibilities, dissociation from offending peers, and experience of victimisation.

The needs of ethnic minority women

The Lammy Review in 2017 highlighted (i) a number of ways in which ethnic minority women were different from ethnic minority men and (ii) areas in which ethnic minority women were treated differently to women from a white background. It was noted that the term BAME has the potential to obfuscate issues, since groups within the BAME category can have different offending profiles and needs from each other. Black women for instance reoffend at lower levels than white women, while black men reoffend at higher levels than white men. A programme designed for ethnic minority people with this high level of reoffending in mind might be entirely inappropriate or even counter-productive for black women.

Lammy also noted how Muslim women could be cut off by their families because of shame – a notable issue bearing in mind the findings of Lord Farmer’s review (see below) about the importance of family links to rehabilitation.

Women’s centres

A regular theme within studies on women’s offending is the good work undertaken by women’s centres and the potential asset they represent for delivering gender-focused services for those under probation supervision. The approach used by women’s centres is to treat women holistically and as individuals, responding practically to their individual needs, rather than focusing solely on cognitive processes. They help the women to build the capacity to address their own issues rather than just addressing offending behaviour.

While there are a range of models for women’s centres, they are commonly multi-agency hubs, providing both a benefit to the women attending and also to the agencies for whom these women have often proved to be a hard to reach group. Importantly these centres are not solely criminal justice agencies and can be involved in the lives of the women that attend them beyond the bounds of the criminal justice system, offering: (i) a preventative measure to help women resolve situations that might lead to offending; and (ii) a follow-up service, maintaining contact after women have finished their terms on probation.

Calls for a more sustainable funding model for women’s centres have been made based on an analysis of relative costs and benefits, for example in comparison to custody.

The importance of family relationships

The 2019 Farmer Review found that relationships were very important to women, affecting the likelihood of reoffending ‘significantly more frequently than is the case for men’. Women are more likely to be primary carers of children, and a large proportion of those in the criminal justice system have been victims of domestic or other abuse. Farmer thus argues that relationships are the ‘foundation stone’ that a woman can ‘build her new life upon’, and that all women need this to be an explicit element in their rehabilitation, even more so where relationships are identified as criminogenic.

The Farmer Review advocates early intervention, finding that there are usually many missed opportunities to prevent later criminality, with a lack of integration between the various services that women might access. Consequently, the necessary information, including details about key relationships, was often not in the hands of the people able to intervene.

![]() Find out more about family relationships

Find out more about family relationships

Relationships with practitioners

Relationships with probation officers can affect how women react to their supervision, particularly as women under supervision tend to have limited social networks. Relationships that are more punitive and less supportive can lead to increased anxiety, which is correlated with higher recidivism. The need for positive relationships which challenge feelings of shame and stigmatisation has been highlighted. Mentoring has also shown promise for women, particularly to help address social capital deficits and provide non-judgemental advice on practical matters.

![]() Find out more about supervision skills

Find out more about supervision skills

In our 2011 thematic inspection of women’s services, we concluded that women’s centres can play an important role in securing engagement with those women who have proven difficult to engage. Some women’s centres allowed women to see their probation officer on site for supervision, ensuring a less stressful setting, particularly for those who had suffered abuse from men. However, we found a great discrepancy in the availability of women’s centres, their opening times, and accessibility across different areas. Funding was often precarious and short term.

Our 2016 inspection of women’s services found that the removal of ring-fenced funding, a lack of targets regarding provision, and a lack of central monitoring had led to an insufficient focus on women and variable performance across areas. Sentencers needed court reports to be more gender specific, with a better understanding of the provision locally available for women. There were gaps in provision in relation to accommodation issues and in terms of the funding of women’s centres which continued to provide an excellent resource. Most women were offered a female probation officer, but the facility to report in female-only environments was not available to all and in some cases this was a barrier to engagement. Safeguarding needs were overlooked in one third of cases, particularly around domestic abuse and exploitation of women, both sexual and otherwise.

All Party Parliamentary Group on Women in the Penal System. (2018). Sentencers and sentenced: exploring knowledge, agency and sentencing women to prison. The Howard League for Penal Reform: London.

Gelsthorpe, L. (2020). ‘What works with women offenders? An English and Welsh perspective’, in Ugwudike, P., Graham, H., McNeill, F., Raynor, P. Taxman, F.S. and Trotter, C. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Rehabilitative Work in Criminal Justice, London: Routledge, pp. 622-632.

Home Office. (2007). The Corston Report: A report by Baroness Jean Corston of a review of women with particular vulnerabilities in the criminal justice system. London: Home Office.

Ministry of Justice. (2019). Farmer review for women. London: Ministry of Justice

Prison Reform Trust. (2021). Why focus on reducing women’s imprisonment? London: Prison Reform Trust.

Rutter, N. and Barr, U. (2021). ‘Being a ‘good woman’: Stigma, relationships and desistance’, Probation Journal, 68(2), pp. 166-185.

Women’s Budget Group. (2020). The Case for Sustainable Funding for Women’s Centres. London: The Women’s Budget Group.

Back to young adults Next: Ethnic minorities