Out-of-court disposals

Key Findings

- There is some tentative evidence of reductions in reoffending and some evidence of schemes being able to deliver efficiency savings.

- Evaluations have found that youth justice service (YJS) staff are enthusiastic about out-of-court models, believing that they produce tangible benefits. Police have been found to be enthusiastic where they are involved, but less so when they have no role beyond referral.

- Victims have been found to be more involved and more positive in the process where restorative justice is used and where police officers act as the victim officer.

- Having a centralised out-of-court process has been found to improve consistency and efficiency in making decisions about children’s disposals.

- Children and their families often find the out-of-court disposal rewarding, both in terms of access to other required services and in helping to prevent further offending.

- There remain questions about ethnic minority children being denied access to out-of-court disposals due to lack of trust of the police and the wider criminal justice system.

Background

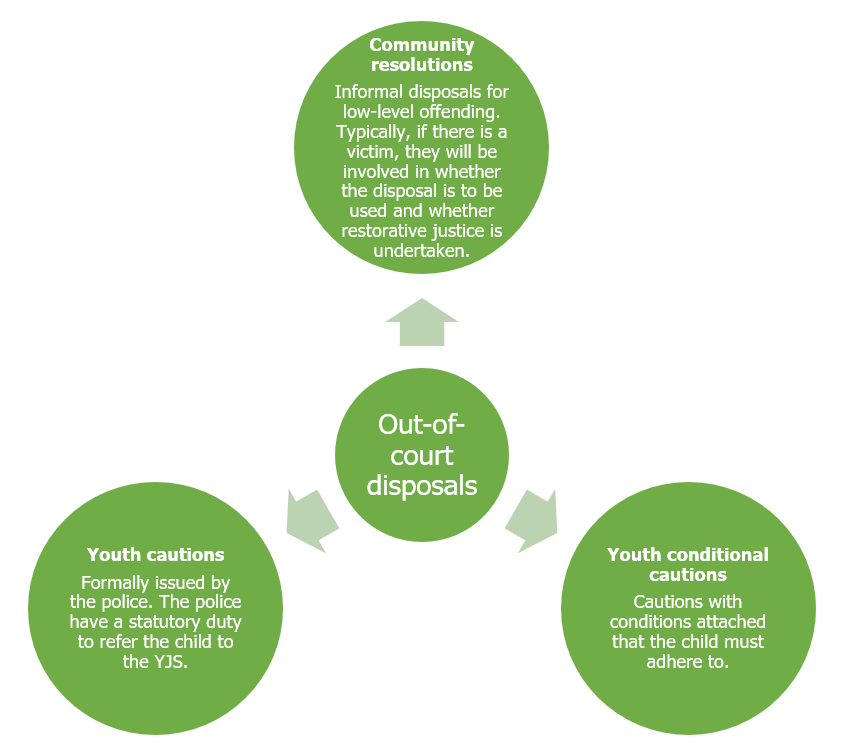

The Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO 2012) replaced reprimands and final warnings with (i) youth cautions, (ii) youth conditional cautions, and (iii) the non-statutory community resolutions. The ethos behind all three of these disposals is to intervene early in the offending career of a child and address their offending behaviour holistically before it becomes entrenched. Particularly when offences are relatively low-level, out-of-court disposals are seen as an appropriate way to avoid costly court appearances and the potential stigmatising effects of entry into the full youth justice system.

Some out-of-court disposals, particularly community resolutions, are delivered on the street, sometimes involving restorative justice to the satisfaction of the victim. However, it is becoming more common for out-of-court disposals to be referred to a joint decision-making body, usually consisting of the local YJS and a police representative, and increasingly other relevant partners such as education and children’s social care, to assess and determine a suitable disposal. There is no limit on the number of times a child can receive an out-of-court disposal, although consideration should always be given to the effectiveness of previous disposals. An admission of guilt or acceptance of responsibility for the offence is required, unlike for the diversionary ‘Outcome 22’ option.

Since 2007, there has been a continual decrease in the number of children in the criminal justice system. This has coincided with a shift in the relative proportions of pre-court and post-court cases in the workload of YJSs, with a move towards the former. Key statistics are as follows:

- between March 2012 and March 2022, there was a 78 per cent drop in the number of children who were first time entrants (including cautions and conditional cautions but not community resolutions) to the criminal justice system

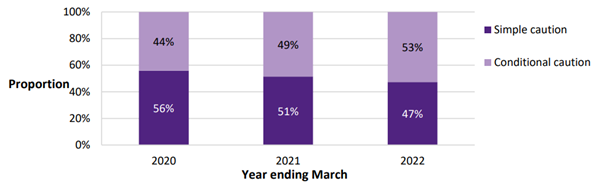

- there was an 88 per cent drop in the number of youth cautions and conditional cautions. As shown by the figure below, there has been a shift in the proportionate use of cautions and conditional cautions, with a greater use of the latter in the year ending March 2022

- in the aggregated cohort for the year ending March 2021, the 12-month reoffending rate for those receiving youth cautions/conditional cautions was 23 per cent.

Statistics and data in relation to informal community resolutions are not currently available, resulting in a significant evidence gap in understanding their use and effectiveness. Offences dealt with through a community resolution are not recorded on the Police National Computer (PNC) and thus will be missing from any reoffending studies based upon PNC data.

Summary of the evidence

Evidence of effectiveness

Research broadly suggests that diverting children from formal court disposals can help to reduce reoffending. The mechanism is somewhat unclear, although studies suggest that there are benefits from avoiding stigmatisation or labelling effects

A 2010 international meta-analysis found that diversion from formal justice produced lower reoffending than formal disposals. There was considerable differences in the types of diversion used, and it was found that diversions which consisted of little more than a warning and release worked better with low-risk cases, while out-of-court disposals with an intervention programme worked better with medium and high-risk children. Although a 2012 meta-analysis found no overall difference between diversion/out-of-court disposals and formal justice, further analysis revealed that certain forms of diversion such as family and restorative justice were associated with reductions in reoffending. An analysis of an Australian scheme found that diversion via cautions produced better reoffending outcomes than sentencing through a youth court, even when it was the individual’s second or third contact with the youth justice system.

Cost savings

Evaluations of out-of-court schemes have usually focused on cost savings to police and local authorities and do not account for cost savings from central budgets such as courts. They also do not include an assessment of the reduction in costs to victims and the wider society from continued reoffending, assuming that the intervention has reduced reoffending. However, some schemes have been found to either save on costs or be cost neutral. Having a single process operated by people who were very familiar with it introduced efficiency savings, even if these were then negated by the more intensive work delivered.

Practitioner views

Evaluations have found that staff from both police and YJSs are receptive to out-of-court disposal schemes, viewing them as superior to earlier approaches. Where police are not involved with the triage process past the police custody stage, the confidence of police officers has been found to be low, but where they are involved, confidence has been found to be high, with the police often highly involved in driving the programme.

In research which explored how YJSs implement and deliver community resolutions, the interviewed managers, case workers, and partner agencies were mostly positive about these disposals and their aim to keep young people away from the more formal justice system as much as possible. The underpinning principles guiding the process were described as ‘child first’ (sometimes referred to as ‘child-led’), ‘trauma-informed’, and ‘restorative’. It was felt that local guidance worked best when co-developed by YJSs, the police, and other relevant agencies. Where the referral practice was reported as good or improving, it was typically the YJS police officer who was connecting and delivering the knowledge exchange between the YJS and the police constabulary. It was also felt that careful consideration should always be given to the merit of issuing multiple resolutions, as participants suggested that this could undermine the disposal and its ability to engage young people, parents, and victims in the process.

The importance of clear communication to the young person, their parent/carer, and the victim, of the decision to give a community resolution was highlighted, helping to avoid confusion about what the disposal involves and what it aims to achieve. Participants suggested that there remained some ambiguity around these initial police communications, supporting previous findings of the need for clarity. The young people themselves spoke positively about the impact of community resolutions on their thinking and behaviour, but also raised feelings of frustration with what they perceived as repetitive sessions.

Victim satisfaction and public opinion

The 2015 Suffolk Enhanced Triage evaluation found that victim uptake of services and satisfaction for those that accepted the offer had increased from the preceding scheme, particularly where police officers filled the role of victim officer, and where restorative justice was used. Where police were not involved in delivering out-of-court disposals beyond the police custody stage, victim satisfaction was much lower and this was attributed to a lack of understanding and enthusiasm on the part of police when dealing with victims. Letters of apology were widely seen as valuable to victims, often helping them to understand why the offence had happened and helping them get a sense of closure.

In a 2021 survey of over 2,000 adults in England and Wales, most responded that they did not know exactly what out-of-court disposals are. When given more information, respondents supported using them for low-level crimes, first-time offenders and those who are vulnerable, including children in care, at risk of exploitation, and struggling with education. There was support for considering the views of victims, and for a justice ‘escalator’ approach – where individuals can be given an out-of-court disposal if they have committed a minor first-time offence, but not where they have already had such a disposal and/or if they have been to court before.

Consistency of process and procedural justice

The 2015 Suffolk Enhanced Triage evaluation found that prior to the scheme, community resolutions were administered by police officers and there was little sense of centralised recording or uniformity of application. The triage system enabled a single process with more consistent judgements and easier monitoring and recording of information, for instance on the outcomes of any previous community resolution a child had received.

The research on community resolutions similarly highlighted the need for national and local consistency in implementing and delivering these disposals (alongside diversionary alternatives, notably ‘Outcome 22’), with clearly defined and consistent referral mechanisms, consistent use of screening tools and assessment, and clear monitoring and evaluation processes. These can be seen as important elements of procedural justice and could contribute to the fairness and hence acceptance of the process by recipients.

Racial disproportionality

Out-of-court disposals can only be made with the admission of guilt by the child for their crime. This is particularly important for any intervention that includes a restorative justice component; all restorative justice interventions must be predicated upon the individual having acknowledged that the offence has occurred and having taken at least some responsibility for it. The 2017 Lammy Review found that there is considerable racial disparity in the youth justice system and that distrust between ethnic minority communities and the justice system could be driving those disparities. Lack of trust of police amongst ethnic minority young people could lead to an unwillingness to admit to being responsible for a crime, which in turn rules out the use of out-of-court disposals and potentially results in more formal court sentences.

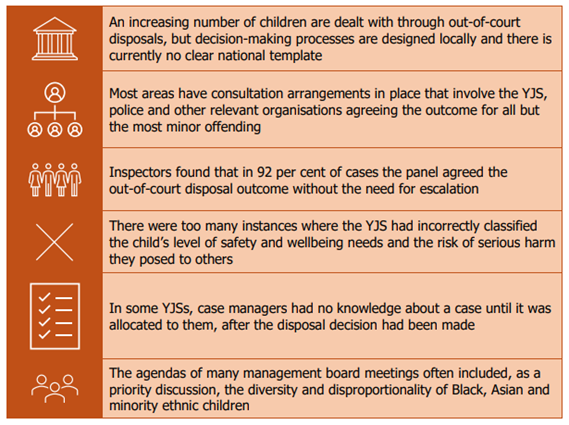

In our Research & Analysis Bulletin 2021/05 (PDF, 531 kB), we focused upon out-of-court disposals, presenting findings from the YJS inspections conducted between June 2018 and February 2020. We found that the best performing YJSs tended to have a robust framework for managing out-of-court disposals, where staff understood their roles and that of their partners and where inter-agency communication was strong. Skilled and engaged board members from other agencies were often able to facilitate effective multi-agency working. Looking across the cases examined by our inspectors, common enablers and barriers to effective delivery of out-of-court disposals were identified. The enablers highlight the importance of: (i) early YJS involvement in decision making; (ii) utilising multiple sources of information to build a complete picture of the child; (iii) ensuring that plans are proportionate and build upon strengths; (iv) coordinating delivery across agencies; and (v) ensuring flexibility in delivery to maximise engagement.

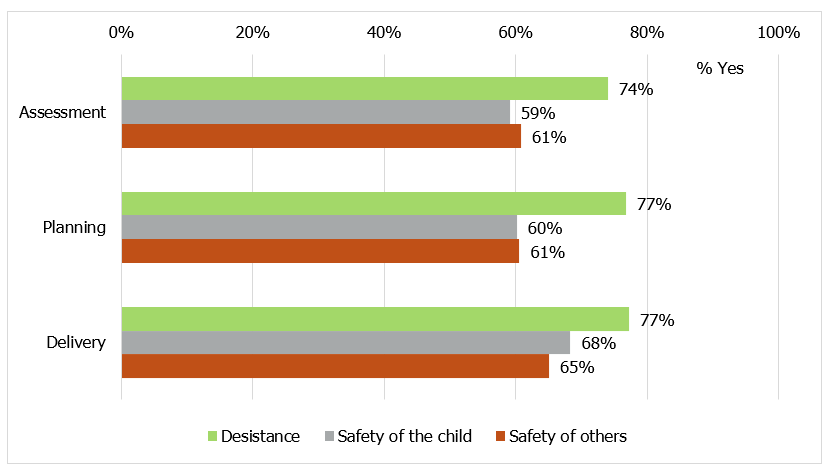

Across those YJSs that were performing less well, shortcomings were found in relation to the levels of communication, recording, performance monitoring, and feedback. A theme running through almost all the poorly performing YJSs was an insufficient focus upon the safety of the child and/or other people. This often commenced at the assessment stage, where there was a focus upon desistance, but insufficient attention given to potential safety issues.

Sufficiency of assessment, planning and delivery in supporting desistance, keeping the child safe and keeping other people safe:

Further analysis revealed that assessment was less likely to be judged sufficient for community resolutions compared to youth conditional cautions. We found instances of assessments not being completed at all, assessments being completed by unqualified or untrained staff, and the use of tools which did not sufficiently consider all relevant circumstances and the full context, hindering a whole-child approach.

More recently, our 2022 Annual Report (PDF, 1 MB) summarised our inspection findings in relation to out-of-court disposals as follows:

Crest Advisory (2022). Reducing flows into the criminal justice system: polling on out-of-court disposals and diversion. London: Crest Advisory.

Haines, K., Case, S., Davies, K. and Charles, A. (2013). ‘The Swansea Bureau: A model of diversion from the Youth Justice System’, International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 41(2), pp. 167-187.

Manning, M. (2015). ‘Enhanced Triage’ an Integrated Decision Making Model. Ipswich: University Campus Suffolk.

Smith, R. (2014). ‘Re-inventing Diversion’, Youth Justice, 14(2), pp. 109-121.

Soppitt, S. and Irving, A. (2014) ‘Triage: line or nets? Early intervention and the youth justice system’, Safer Communities, 13(4), pp. 147-160.

Wilson, H.A. and Hoge, R. D. (2012). ‘The effect of youth diversion programs on recidivism: A meta-analytic review’, Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40, pp. 497-518.

Back to Specific types of delivery Next: Youth courts

Last updated: 27 October 2023