Child-friendly justice

Key findings

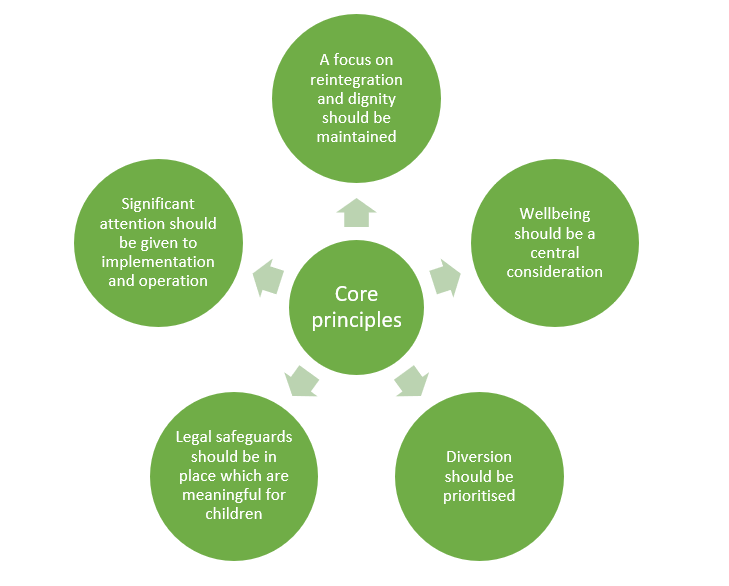

- Key criteria have been identified for a child-friendly, rights-compliant youth justice system, encompassing children’s reintegration, dignity and wellbeing, a prioritisation of diversion, the incorporation of legal safeguards, and a focus upon implementation and operation.

- There is an emphasis on meaningful participation where children are able to speak their mind and give their views in all matters that affect them, with their opinions being taken into account seriously and given due respect.

- To pursue a child-friendly, rights-compliant model of restorative justice, processes must be limited in their intensity, prioritise children’s rights, and used to divert children from adversarial processes.

Background

Child-friendly justice, which highlights the importance of social justice responses, has its origins in international human rights legal frameworks. Notably, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) sets out foundational principles for an approach to youth justice that is child-friendly, strengths-based and centred on participatory practice with children. The UNCRC specifies that the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration and refers to the desirability of promoting the child’s reintegration.

In 2010, the Council of Europe issued Guidelines on child-friendly justice. These ‘guidelines’ articulate a range of further human rights-based principles that serve both to frame the concept of ‘child friendly justice’ and echo the general provisions of the UNCRC. Best interest principles are re-emphasised and there is a focus on the importance of enabling the participation of children and recognising their dignity.

Summary of the evidence

A balanced approach

The international standards relating to children in conflict with the law emphasise the need to treat children as children, and not simply as lawbreakers. Building on this foundational principle, it is equally clear that ensuring adequate procedural rights and concerns related to children’s wellbeing are fundamentally inter-dependent. It has been argued that strong protection for children’s rights is essential to secure wellbeing, while ensuring that children’s needs are met may be an essential pre-requisite for ensuring that their procedural rights are meaningful.

Five key criteria have been identified for a rights-compliant youth justice system:

- focus on reintegration and dignity rather than punitiveness: there is a requirement not only that overly-punitive approaches are avoided, but that children’s reintegration and assumption of a positive role in society are key underlying goals

- the wellbeing of children in conflict with the law: in considering the overall approach to youth justice, a key criterion for assessing the level of rights-compliance must be how space is created for consideration of the needs and wellbeing of the child

- diversion: there should be a focus on encouraging diversion, but with attention to children’s due process rights and the processes of implementation

- procedural rights: a rights-compliant youth justice system requires the provision of adequate legal safeguards, adapted so that they can be meaningful for children in practice

- implementation: significant attention needs to be given to the implementation and operation of youth justice in practice. Key elements are adequate law and policy frameworks, adequate systems of governance, including effective systems of co-ordination and co-operation, adequate infrastructure and the training of professionals.

It has also been recognised that serious consideration needs to be given to the difficulties encountered by all systems of youth justice to deal in an age-appropriate and rights-compliant way with older children and those who commit serious offences.

Participation of the child

Research demonstrates that children can feel ignored or misrepresented, as though their experiences do not matter. Listening to children can provide valuable insights, and the Council of Europe guidelines emphasise the importance of meaningful participation where children are able to speak their mind and give their views in all matters that affect them, with their opinions being taken into account seriously and given due respect.

In developing the guidelines on child-friendly justice, the views of children were obtained through a survey (almost 3,800 questionnaires were returned from 25 countries) and focus groups. When asked about the key messages for the guidelines, children highlighted the following:

- being treated with respect

- being listened to

- being provided with explanations in language they understand

- receiving information about their rights.

A recent example of meaningful participation can be found in Greater Manchester, where justice-involved children helped to co-create a transformative framework of practice, termed Participatory Youth Practice (PYP). A number of essential ingredients were identified, including fostering equitable relationships, gaining trust, creating safe spaces, ensuring clarity of purpose, and investing the necessary time and resources. The final framework consisted of the following eight principles:

- let them participate

- always unpick why

- acknowledge limited life chances

- try to avoid threats and sanctions

- help problem solve

- help them find better options

- develop their ambitions

- remember that ultimately it’s their choice.

Restorative approaches

Many international agreements now strongly promote the development of restorative justice. To pursue a child-friendly, rights-compliant model of practice, in line with the research evidence, restorative justice processes must be limited in their intensity, prioritise children’s rights, and used to divert children from punitive outcomes and adversarial processes.

Restorative practices should also enable the active participation of children and seek to promote more participatory and collaborative forms of decision-making.

Forde, L. (2021). ‘Welfare, Justice, and Diverse Models of Youth Justice: A Children’s Rights Analysis’, The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 29(4), pp. 920-945.

Kilkelly, U. (2010). Listening to children about justice: Report of the Council of Europe consultation with children on child-friendly justice, CJ-S-CH (2010) 14 rev. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Marder, I.D. and Forder, L. (2022). ‘Challenges in the Future of Restorative Youth Justice in Ireland: Minimising Intervention, Maximising Participation’, Youth Justice.

Back to General models and principles Next: Social-ecological framework

Last updated: 10 March 2023