The Risk-Need-Responsivity Model

Key findings

- Adherence to the risk, need and responsivity principles has been found to be associated with reductions in reoffending, particularly for delivery in community settings.

- Eight offending-related needs have been identified, seven of which are dynamic in nature.

- There is evidence supporting the use of cognitive behavioural programmes, targeted to individuals with higher risk scores, that teach skills such as emotional regulation and perspective taking.

Background

The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model has become the leading model of offender assessment and treatment in the world. It now includes 15 principles, grouped into:

(i) overarching principles

(ii) core RNR principles and key clinical issues

(iii) organisational principles.

The three core RNR principles are as follows:

- risk is about whom to target, based upon an individual’s likelihood of reoffending. This is important because interventions should match the likelihood of reoffending – rehabilitative interventions should be offered to moderate and high-risk cases, with low-risk cases receiving minimal intervention

- need is about what should be done – identified criminogenic needs should be the focus of targeted interventions, rather than other needs which are not related to offending behaviour

- responsivity is about how the work should be delivered, covering both general and specific responsivity. While general responsivity promotes the use of cognitive social learning methods to influence behaviour, specific responsivity provides that interventions should be tailored to, amongst other things, the strengths of the individual. Supervision skills are an aspect of responsivity.

Summary of the evidence

Reductions in reoffending

Adherence to the core RNR principles has been found to be associated with reductions in reoffending. Looking across studies, adherence to all three principles has been found to result in a 17 per cent positive difference in average recidivism between treated and non-treated offenders when delivered in residential/custodial settings, and a 35 per cent difference when delivered in community settings. In contrast, recidivism increased when there was a failure to adhere to any of the RNR principles, i.e. if treatment targeted non-criminogenic needs of low risk offenders using non-cognitive-behavioural techniques.

Offending-related needs

Offending-related or criminogenic needs are those dynamic factors which independently contribute to or are supportive of offending. Studies have examined which factors are linked to reoffending, whether changes in these factors lead to changes in reoffending, and whether this holds true when taking into account the associations between factors.

A review of the current literature has identified the following ‘central eight’ risk/need factors, the final seven of which are dynamic and amenable to change:

- criminal history

- pro-criminal attitudes

- pro-criminal associates

- anti-social personality pattern

- family/marital

- school/work

- substance abuse

- leisure/recreation.

Effective interventions

A range of research studies have reported positive outcomes for programmes described as cognitive behavioural, targeted to individuals with higher risk scores, that teach skills such as emotional regulation and perspective taking.

Research findings also indicate that some approaches do not ‘work’. For example, ‘Scared Straight’ type programmes, which have a focus on deterrence, have been found to either have no impact or often a negative impact.

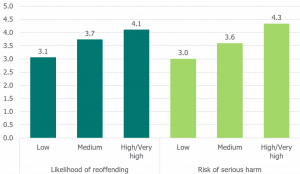

In our full round of probation inspections completed during 2018/2019, we examined over 3,000 cases. Within this sample, the need most frequently identified by inspectors was thinking and behaviour, recorded in over four-fifths (84 per cent) of the inspected cases. Lifestyle was the next most frequently identified need; just over half (53 per cent) of the cases. In nearly half (47 per cent) of the cases, it was judged that the service user had four or more needs, highlighting how often careful attention needs to be paid to the sequencing and alignment of interventions. The strongest relationship was between drug misuse and lifestyle – both were present in a third (33 per cent) of the cases.

The figure below sets out how the average number of needs increased across the risk levels.

Bonta, J. and Andrews, D.A. (2017). The Psychology of Criminal Conduct. London: Routledge.

Ministry of Justice (2014). Transforming Rehabilitation: a summary of evidence on reducing reoffending. London: Ministry of Justice

O’Donnell, I. (2020). An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses. Dublin. Department of Justice and Equality.

Back to Models and principles Next: Desistance

Last updated: 18 December 2020